What Happened to the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel ?

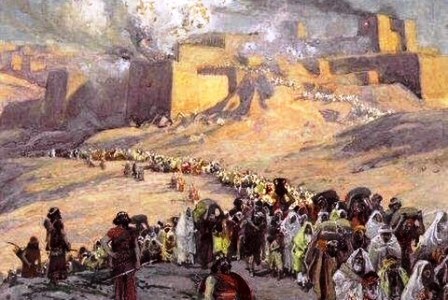

Historical books of the Bible tell us that when the Assyrians invades the Kingdom of Israel between 724 and 721, they deport ten of the twelve tribes making up the Hebrews. No one knows what becomes of these ten lost tribes and, from Antiquity to the 19th century, many travelers claim to have found them.

In exile

In 930, the Kingdom of David and Solomon split into two states: the Kingdom of Israel, in the north, made up of ten tribes, and the Kingdom of Judah, in the south, where the two other tribes met. Israel fell in 721 under Assyrian pressure and its inhabitants were exiled to "Halah and on the Habor, the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes" (II Kings, 17). They then disappear from history.

An announced return

During Antiquity and the period of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, no one doubts the existence of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Tradition attributes their incapacity to join their brothers to the fact that the two tribes of the Kingdom of Judah are dispersed throughout the world. The ten tribes are exiled beyond the mysterious Sambation River, the crossing of which is only possible on the Sabbath. In addition, according to the Jerusalem Talmud, the exiles were divided into three equal groups, and each took a different direction.

From the Middle Ages to the present day, many travelers and explorers declared having found the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. In the ninth century, a man arises, Eldad ha-Dani, who declares that he is a member of the tribe of Dan, and knows four of the ten tribes. Another adventurer, David Reubeni, claims to be the brother of Joseph, king of the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh, who were at that time settled in Khaybar, Arabia. The name of Khaybar is without a doubt inspired by Habor, a city mentioned in the Bible. Finally, in 1173, the traveler Benjamin of Tudela, the first European to return from China, described the lost tribes at length. Four of them, those of Dan, Asher, Zebulun and Naphtali, were, he said, based in the city of Nishapur, Asia, where they would be governed by "their own Prince Joseph Amarkala the Levite".

From Ethiopia to America

The kabbalist Abraham Levi, saw, in 1528, the descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes in the Falashas, black population of Judaic religion living in Ethiopia. But it’s unlikely. Ethiopia and Egypt have always had close relations, and the Hebrews have long been numerous in Egypt: some of them quite naturally converted a group of Ethiopians to their religion.

The most fantastic hypothesis was put forward in the 17th century by a traveler from Amsterdam, Antonio de Montezinos. Returning from a trip to South America, he says that Indians in the Andean Mountains welcomed him by reciting the Shema, a prayer made up of three verses from the Torah. Menasseh ben Israel, rabbi of Amsterdam, is won over by the story of Montezinos. He publishes in 1652 a book, Hope of Israel, in which he writes: "The West Indies have been inhabited for a long time by a part of the Ten Lost Tribes, passed on the other side of Tartary by the Strait of Anian" (Current Bering Strait). Naturally, no later exploration confirms this dream. In his Two Journeys to Jerusalem, published in Glasgow in 1786, it was in the North American Indians that the Englishman Richard Burton (Nathaniel Crouch) recognized the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Whoever wants to follow him must admit that the religious practices of the Hebrews who became Sioux have notably evolved!

The lost tribes found

Twentieth century archaeologists and the study of Assyrian texts are helping to re-establish the truth today. In 721, Samaria was taken by the Assyrian king Sargon. He deported part of the population in Assyria and replaced them with Mesopotamians. But, contrary to the accounts of the Hebrew tradition, the ten tribes do not disappear in exile. The Bible frequently mentions the large populations that remained in Israel.

Only a very small part of the Hebrews are forced to take the road to Assyria: 27,280 people in four years, according to the archives of Sargon. But these are the ruling classes: priests, civil servants, intellectuals. If they are a minority, they are the ones who inspire culture and politics, which is why they are replaced by the Assyrian administration. There is therefore no mass physical deportation and disappearance of the tribes, as has long been believed, but an intellectual extinction of the identity of these tribes.

Early Hebrews

The history of the Hebrews begins with Abraham, a Sumerian who, around 1700 BC, leaves the city of Ur with his clan. He moved to Canaan. Over the centuries, the clan became a powerful semi-nomadic tribe which maintained good relations with Egypt.

But around 1675 the pharaohs were overthrown by the Hyksos. The Hebrews line up alongside the invaders and settle in Egypt. When the Hyksos were repulsed in 1580, the Hebrews, guilty of treason in the eyes of the Egyptians, were held captive. About two centuries later, probably under the reign of Akhenaten, they left Egypt under the leadership of an Egyptian noble of Jewish origin, Moses, who was the first to actually codify the religion.

They conquer and colonize Canaan, from where they expel the indigenous Semitic tribes. They install a tribal democracy, replaced in 1020 by a monarchy. After the reign of Solomon (970-930), the kingdom split into two: Israel and its ten tribes in the North, Judah and its two tribes in the South. The two states are shaken by serious political crises; in the North, these crises facilitate the Assyrian invasion, which occurs after 724.