Tell el-Amarna

The Valley of the Kings Abandoned ?

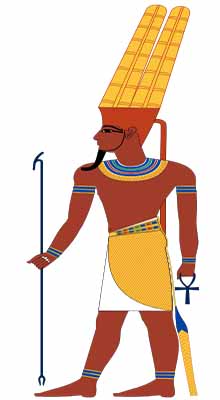

It is in the sacred city of Tell el-Amarna that the pharaoh Akhenaten (Amenophis IV) carried out what can be defined as the first religious revolution in history. Akhenaten was, in fact, the first and only Egyptian king who decided to abolish polytheistic worship and replace it with monotheism. Considered heretical by the priests, Amenophis IV reigned first alongside his father, then alone (from 1350 to 1335 BC).

A new monotheistic religion

The pharaoh imposed the transition from polytheism to monotheism, by replacing the traditional gods with one and only one god: Aten, name which means “solar disk”. He also changed his name Amenhotep (which means “Amun is gracious”) to Akhenaten (“the servant of Aten”). The high priest of Amun, the national god, was thus deprived of his possessions and his powers, which caused great discontent in the upper religious spheres.

According to a theological path directly inspired by the god (Amenophis IV claimed to be the prophet of Aten), the new religion exalted universal harmony, the beauty of nature and love between men. In an Egypt dominated by the cult of power and materialism, this new religion made few followers. When Amenophis IV became pharaoh, the country was at the height of its power. Under the guide of some prestigious sovereigns (the Thutmose dynasty), the children of the Nile had embarked on a great policy of conquests, extending their domination in the east over Palestine, Syria and as far as the Euphrates.

The Valley of the Kings at the center of the ancient polytheistic religion

The image of the “land of the pharaohs” who had built its power around the pyramids was only a memory of the past: during the New Empire (1580-1090), Egypt had acquired international prestige, with an army among the most organized and motivated, and a well-developed commercial network, which guaranteed the empire favorable exchanges with the most distant countries. With this wealth, the court led a luxurious life, as evidenced by the art of this period. The city of Thebes, located in the famous Valley of the Kings, was the center of religious power; it was dedicated to Amun, king of the gods (Amun-Ra) and absolute deity of Upper and Lower Egypt, whose worship was celebrated in the great temple of Karnak. Thanks to the incredible privileges which they enjoyed, the priests of the God Amun constituted a kind of small state apart: first example, perhaps, of the old opposition between spiritual power and temporal power. The end of the reign of Amenhotep III, father of Akhenaten, had already been marked by a certain decadence: the greatness and the splendor which had characterized this era seemed to be disturbed by the absence of spirituality, of internal authorities creating values. It is this sense of spirituality that tried to restore Amenophis IV by founding what could be defined as the first heresy in the history of religions.

Tell el-Amarna the new capital

The name of Amun was erased from the temple doors and the court abandoned Thebes. They then built a new capital (one of the masterpieces of Egyptian architecture, with wide streets, residential areas, temples, and a fairly innovative urban structure) located further north, near present-day Tell el-Amarna. Meanwhile, the pharaoh, supported by his wife Nefertiti, continued his action to suppress polytheism in favor of the monotheistic cult of Aten.

Aten, city of the sun

The action of man and sand destroyed the great temples and palaces of the capital built by the heretical pharaoh. About 40 kilometers from Beni Hassan, today you can visit the remains of Tell el-Amarna, which made it possible to reconstruct the old city on paper, the epicenter of an innovative monotheism. It was along the Nile that the pharaoh's palace, the great temple, the palace of Aten and the city proper were built. Further south, a temple stood on the river, while the tombs, facing east, were distributed to the north and south of the site. None of these tombs were completed, and it is believed that they were never used.

Located to the north at the palace of Tell el-Amarna, in the middle of an enclosure of 800 meters x 300 meters, the great temple was formed inside a set of successive courtyards. The architecture of the sanctuary was different from classical Egyptian architecture. Unlike Luxor or Karnak, where the sanctuary was a secret room reserved for rites and whose access was reserved for the pharaoh and the priests, the sanctuary of Aten was open and devoid of any structure capable of preventing the entry of the sunlight. Akhenaten had wished, moreover, that all the architecture of the capital reflect the openness to the great monotheistic cult. The pharaoh's desire was to free himself, but especially other men, from the burden of earthly limits, indicating the way to rise and listen to the divine voice. He ends up being alone, locked in his palace of Tell el-Amarna, surrounded by a handful of the faithful. Meanwhile, outside, great Egypt, colonialist and belligerent, deprived of the protection of its polytheistic pantheon, as well as a guide, lost its splendor.

Amun celebrated again

Akhenaten's great dream was about to come to an end, restoration was necessary and reason of State prevailed over spiritual authorities. Amenophis IV having no son, his brother Tutankhamen succeeded him. He continued the restoration work until he changed his name to Tutankhamun, thus sealing the return to the past. His reign was brief, however, and after "the pharaoh child", the pharaohs of the new dynasty were all warriors. The lost lands were reconquered, the vassals regained confidence. Amun was again celebrated with lavish rites, the many local deities regained their faithful and the clergy regained lost power. Pharaoh Horemheb, whose personality was ironically sketched by Mika Waltari in The Egyptian, condemned the memory of Amenophis and Tutankhamun, erasing their names from all monuments and steles. But the few scissor blows that mutilated the cartridges did not succeed in erasing the memory of the rather short reign of a brave pharaoh. Nor did they manage to dampen the resonance of a heresy capable of suggesting this idea of harmony which today, after more than 3,000 years, pushes man not to be satisfied only with his daily existence.