What Agitated the Convulsionaries of Saint-Médard ?

Around the tomb of a deacon, in the Saint-Médard cemetery in Paris, between 1727 and 1732, "miraculous" healings and crises of devotion took place in succession, resulting in bodily convulsions.

An extension of the Jansenist quarrel?

The man through whom the scandal happened, the deacon François de Pâris, died in 1727, at the age of 37. His life inspired such respect in the small Parisian people, with whom he had chosen to live, that he died, as they say, in "the odor of holiness". He constantly practiced asceticism and charity. However, this man with an exemplary destiny is an active member of the Jansenists.

In principle, the Jansenist affair has been closed since the condemnation of heresy by the papal bull Unigenitus (1713). This text, rejecting the great theses on grace and predestination specific to the Jansenists, did not succeed in reducing them to silence in France. Jansenism is no longer just in this country a theological debate reserved for the elite: it has become democratized. The small townspeople are no longer unaware of it, and it venerates the Jansenist clergy for their devotion.

Then, under the Regency, a party of bishops, monks, priests and even lay people was formed who "appealed" to the text of Unigenitus to the Pope, hence their name of "appellants". Several of these leaders were excommunicated or deposed after the appeals of 1717, 1720 and 1727. However, François de Pâris signed them all! Can we recognize the holiness of someone belonging to a party condemned by the Church and by the authorities?

First of all "miracles" ...

The first "miraculous" healings took place around the tomb of Paris as early as 1727. The cemetery quickly became the meeting place for a crowd of candidates for healing and ordinary spectators, from all walks of life. People come to lie on the tombstone to be treated and some harvest the earth around the monument to make balms or plasters.

On July 15, 1731, a controversy began: while the Jansenists took advantage of the publicity that these miracles brought them, the Archbishop of Paris affirmed, in a mandate, that they were false and that this cult of relics must cease. Twenty-three Parisian priests then sent him a request to have four miracles recognized on which they had a solid record of testimonies. But the religious authorities respond with silence.

Then convulsions

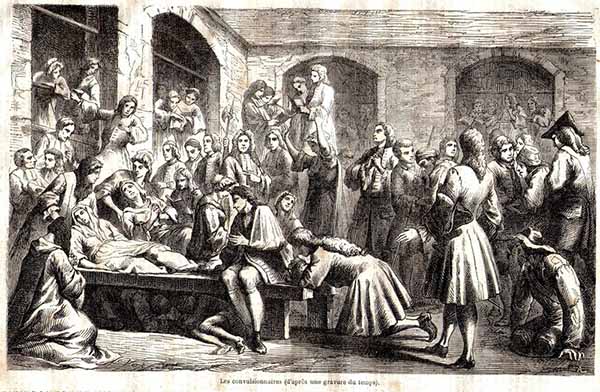

The nature of the phenomenon then changes. "Healings" now take place through long and painful fits of convulsions, hence the name of convulsionaries. These fits of uncontrolled tremors, accompanied by howls and cracks of bones, are very impressive. The subjects' bodies are as if possessed, twisted and pulled in all directions by a mysterious force which tears them out of disorderly movements. The eyes are rolled back, the mouth foaming.

The sometimes scabrous effect of these scenes did not escape the King's police: "What is most scandalous," said an informer, "is to see there young girls who are quite pretty and well made between the arms of men who, by helping them, can satisfy certain passions, for they are two or three hours away, their throats and breasts uncovered, their skirts low, their legs in the air... "

Called on to judge, the king's doctors saw in the phenomenon nothing but a sham. For fear of disturbances, the cemetery was closed on January 29, 1732.

The story does not end there

Some convulsionaries continue to perform at their homes, in cellars or in bourgeois salons. The seizures change in nature: the subjects' bodies are taken by violent contractions which horribly tie the muscles. The convulsion becomes a real torture. The absolute and suffocating stiffness of the body represents the passion of Christ: the help of the spectators, who trample, strike the convulsive man and desperately stretch his limbs to try to relax them, is a torture. This suffering would be the price that subjects pay to demonstrate, alone against all, the veracity of "miracles".

We are moving further and further away from the Paris affair, and the convulsionaries, imprisoned, condemned by parliament and even by the Jansenists, are marginalized and deprived of support. Now they demand to be treated with an iron bar, a sword, a sharp object ...

The ultimate mortification: the crucifixion

From 1745, there are only a few clandestine convulsion communities. The indifference of the authorities, the clergy and the public leads to one last bidding: the crucifixion. Some do it regularly. This is the supreme ordeal, supposed to be total identification with the body of the Suppliciated Redeemer.

Finally, from 1789, we no longer hear of the Convulsionaries of Saint-Médard.