Famous Ancient Cave Paintings of Lascaux France & Altamira

Both the first expression of the artistic genius of humanity and the manifestation of its spiritual dimension, the decorated caves of prehistory, the oldest art in the world, have not revealed all their secrets.

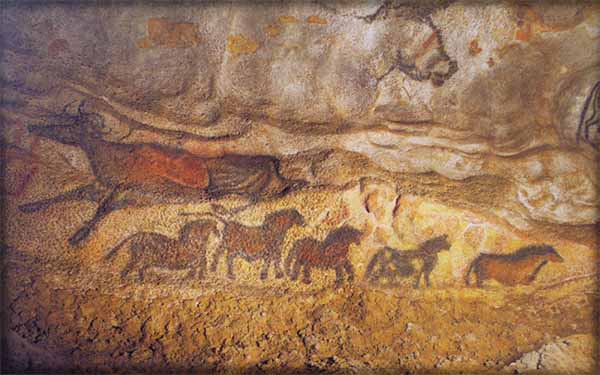

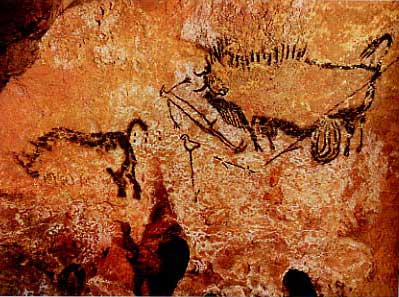

Lascaux and Altamira

In 1879, a 5-year-old girl, who accompanied her father on a visit to a cave in Altamira, Spain, discovered strange painted animals: the cave art of Paleolithic hunters appeared for the first time. Since then, other discoveries, many in Lascaux in the south of France, have followed. But, despite new, more refined methods of analysis, it was necessary to overcome many ideological prejudices in order to try to interpret and give a meaning to them.

History of prehistoric art and stone age cave painting

Cave art originated around 30,000 BCE, but it did not really flourish until between 20,000 and 12,000 BCE, at the end of the Upper Paleolithic. The first pictorial manifestations, around 30,000, were first stylized drawings carved in the rock, linked to the emerging cult of the mother goddess, with sexual connotations (vulva). From -24,000 to -22,000, monochrome engravings and paintings appear (mammoths and woolly rhinos). Around -20,000, the peak of the last ice age, we witness the proliferation of cave art and the start of ritual ceremonies. The first polychrome cave paintings, as in Lascaux, appear around -18,000, then, from -15,000, they become more elaborate, reaching their peak around -13,000 with reliefs and naturalistic, monochrome and polychrome paintings. Finally, around 12,000 years BCE, cave art disappears in Altamira, ironically, where it all began for us. In all, no less than 300 Paleolithic caves, containing paintings and parietal reliefs, are spread over a geographical area limited to the south of France and the north of Spain.

A favorable period

The appearance of ancient cave art corresponds to a period of climatic upheavals, but also of unprecedented social and technological innovations. Demography is increasing, exchanges between populations are intensifying and concern increasingly distant regions, a new lithic industry is developing: tools on blades, flint tools with dual functions, various chisels; new hunting weapons are used: harpoons, spears, thrusters. Finally, the first burials with deposits of weapons and ornaments bear witness to a new approach to death.

This geographic, demographic, economic and social concentration is due to a sedentarization of nomads - who had already developed an older, movable art, which often accompanies rock art - in an area with a more temperate climate, near the Atlantic coasts where there are many fish and edible plants. The decline in wildlife or its migration to high latitudes may also explain the new importance of fishing and farming. Special conditions of development therefore contribute to the emergence of cave art in a determined geographical area.

True prehistoric chic

However, it remains to give meaning to these artistic frescoes. Once the first moments of disbelief have passed, the scholars who have come to admire these prehistoric paintings cry foul. But after Altamira, the discoveries multiplied: La Mouthe in 1895, Combarelles and Font-de-Gaume in 1901, while waiting for Lascaux cave discovery in 1940.

At the start of the 20th century, there was no longer any doubt that primitive men painted this fantastic bestiary deep in caves believed to be a habitat. The period is then strongly influenced by the theory of "art for the sake of art", which favors a purely aesthetic analysis: these representations would therefore only reveal the desire of Paleolithic hunters to surround themselves with beauty in their daily environment. It is fine to be a cavemen, one does not take less care of its interior… And the fact that the great majority of the decorated caves are located on - or under - the French ground will flatter the cockade pride of some who will not fail to salute here the first manifestation of the artistic genius of France which would mark the advent of the history of art! But prehistoric science structuring itself and refining its methods of analysis, under the leadership of Abbé Breuil and especially André Leroi-Gourhan, we soon offered very different interpretations, which began to clarify the mystery, without ever totally dispel it.

Caves that are sanctuaries

Contrary to popular belief, caves are not habitat. Paleolithic men lived in shelters under rocks, and undoubtedly in branch huts, sketches of the first houses. These caves where they painted, and access to which is never decorated, are particularly difficult to access and go deep underground. Thus, at Tuc-d'Audoubert, in Ariège, you have to walk more than 700 meters of a perilous path to discover statuettes of bison modeled in clay. Other caves are only accessible after crossing many natural obstacles. The impression each time is that of a crypt, of a place kept hidden and that one only visits occasionally. There took place a primitive cult which united man and nature in mysterious ceremonies. To try to understand the meaning and purposes of these ceremonies, it will be necessary to appeal to the human sciences, and particularly to ethnology.

The spirit of the shaman

To explain the complex ritual system of a universe of beliefs specific to Cro-Magnon men, researchers will use their knowledge of traditional cultures, mainly African, where the phenomena of totemism have been described at length. The decorated Paleolithic cave then appears as a place of worship for a tribe or clan gathered around a totem representing an ancestor. But it is above all the study of the aborigines of Australia, whose rock paintings express a complex but better known mythology, of the Inuit, hunter-gatherers of the arctic and sub-arctic regions, or even of the reindeer hunters of North-East Asia which brings the interpretation best accepted today: shamanism. The shaman maintains a privileged relationship with the supernatural, the community requests him to intervene with the spirits during illnesses or difficulties, such as the absence of game or a conflict with another tribe. The famous "sorcerer" of the Trois-Frères cave, in Ariège, at the same time deer, man and wolf, would he not be one of those shamans dressed in animal skins, engaging in some ritual dance, and symbolizing, according to Father Breuil, "the Spirit governing the multiplication of game and hunting expeditions"?

World order

André Leroi-Gourhan will offer another explanation by noting that the animals most often represented (horses and bison) are not those (reindeer and deer) which constituted the main diet of these men. In addition, hunting scenes featuring men are extremely rare. Engraved signs, symbolizing the female sex (split triangle) or male (vertical line) often accompany the paintings, and for the prehistorian these signs of a sexual nature (vulva and phallus) are associated with this or that animal according to a strict order. We can also see at Pech Merle a series of five engravings in which a ruminant is transformed into a female silhouette.

The very location of the various animal representations in a cave seems to reflect an intention. Thus horses, mammoths or bison are almost always located on large panels in the center of the cave. On the other hand, deer are mostly represented at the entrance, while the bear is only represented deep in the caves. In Lascaux, Niaux, Cosquer or in the Chauvet cave would therefore be read, according to male and female principles, the order of the world as it was perceived by Paleolithic men.

Initiation rites and the fight against death

Gathered in these caves, prehistoric hunters are also said to have engaged in initiation or passage rites. This hypothesis is confirmed when we look at features more specific to these rites that mark birth, puberty, marriage and death. Indeed, the dances which usually accompany them have the essential function of revealing the mysteries of the adult world. These adolescent rites, which take the form of experiencing boundaries through painful practices (circumcision or tattoos), often take place in seclusion and darkness, away from the community. On the other hand, flutes and other musical instruments have been found as well as traces of the feet of adolescents which suggest a choreography (in Ariège, in the cave of Niaux, more than 500 steps of children of thirteen at fifteen; in that of Tuc-d'Audoubert, footprints of six children in six rows). It is certain that the danger, the emotion were an important part of the ritual.

Thus, Paleolithic rock art would reflect the spirituality of Cro-Magnon men. No doubt it is the expression of an adaptation to the community requirements of a social life which is becoming more complex, and whose beliefs, ceremonies and rites ensure social cohesion, protection and the transmission of values for the survival of the group.

Impressive sites

To create the earliest masterpieces that adorn the caves, Palaeolithic men set up real "sites" at the bottom of them that modern study and observation techniques can reconstruct. The lighting, first of all, essential, was obtained using rudimentary or more elaborate oil lamps like the one found at Lascaux, the handle of which is decorated with the same signs found on the walls. To reach the highest places (sometimes up to 7 meters), it was necessary to erect solid scaffolding, which implies, for some particularly difficult to access caves, rigorous logistics which reflects the importance given to such a business. The colors were obtained using ground pigments (iron oxide, manganese) and mixed with potassium feldspar, bound with oils and animal fats. The artist's tools were varied: brushes, bamboo sticks, brushes, vegetable stamps, stone smoothers ... Far from being an art of pleasure, the decoration of the caves therefore implied an impressive know-how that required community perfect organization and transmission of knowledge.

Enigmatic hands

Among the most moving testimonies preserved in the decorated caves, there are these painted hands with spread fingers that can be seen at Pech Merle, in the Cosquer cave or even in Gargas which contains no less than 150. Made in a stencil (the artist has blown the paint around with his own hand) or plastered on the wall, red or black, sometimes enhanced with symbolic signs, are they simply the artist's signature? Arranged in series or isolated in places that are difficult to access, they also seem to be a mark of identification for an entire group, unless they represent, as a kind of first scriptural sign, the human being, moreover strangely absent in the works. cave decorations. No one has yet been able to unravel the mystery of these hands, painted 20,000 years ago and which still seem to beckon us.