Is the Tomb of Alexander the Great in Alexandria ?

Political ambitions are unleashed around the royal sarcophagus, which keeps changing territory. A curious treasure hunt in the sands of Egypt. To your compasses!

Where can we hope to identify the traces of the Conqueror's burial, which his exploits made immortal? In Memphis, that is, in Saqqara? In the Siwa Oasis, or in Bahariya? In Macedonia, in Verghina? In Lebanon, on the site of ancient Sidon, and, consequently, today in Istanbul? Or in London, even in Venice? Ultimate hypothesis: Alexandria, but where to look in this huge city? To this question, put back on the agenda by the discovery, in 1977, of what may be the tomb of Philip II of Macedonia, the father of Alexander, the cinema but also novels and comics never cease to provide answers that are all the more diverse and fanciful as science has not yet solved the mystery of the location of Alexander the Great’s tomb.

How did Alexander the Great die?

To see more clearly, we have to go back to where it all began. In Babylon, June 10, 323 BC. That day, after ten days of sudden illness, Alexander died at the age of 32; when he was already half-unconscious, he greeted his soldiers with his eyes without being able to say a word. What did the king die of, he who had so often escaped the most terrible dangers? The hypothesis of poisoning, raised since Antiquity, hardly holds, so much the disturbances and the dissensions which will follow show that nothing had been envisaged. The symptoms described by ancient writers, which are based on witness descriptions of the events and on the Official Journal kept at the court of Babylon, suggest, according to the opinions of current medical specialists, that the sovereign, overworked by ten years of uninterrupted effort, may have been the victim of an acute attack of typhoid fever or malaria. Fifteen days before falling ill, Alexander the Great had visited at length the diversion channels of the Euphrates, south of Babylon, and in this very marshy area, he could very well have been bitten by anopheles mosquitoes, transmitters of these terrible diseases.

All kinds of intrigues

His generals take several days to agree on his succession. However, according to all witnesses, the embalmers responsible for taking care of the body of Alexander the Great found it in a perfect state of preservation, despite the heat that reigns in this month of June. Miracle invented to suggest that the king is already more than a man? It is now explained by the deep coma which can characterize the final phase of malaria or typhoid fever. Alexander was still clinically alive several days after his official death, and had probably only passed away when the embalmers arrived.

Around his remains, ambitions are unleashed. All the more so since Alexander died without leaving a legitimate son. He does have a half-brother, Arrhidaeus, but he is weak-minded. And if Roxana, the king's widow, is pregnant, she is not Macedonian, and it is to be hoped that she will give birth to a boy, the only possible successor. The epic era is over. Begin the days of permanent betrayal, of assassination as a means of government, of intrigues of all kinds and of the clash of rival ambitions between those who will be called the diadochi, the heirs of Alexander the Great. For now, the strong men are those to whom the Conqueror has entrusted the highest responsibilities: Perdiccas, whom he appointed first of his advisers after the death of his friend Hephaestion; Craterus, respected by all, but which is then on its way to Europe, where he brings back Macedonian veterans who had obtained their leave; the old Antipater, also absent because responsible for managing Macedonia and Greece; but there are also Ptolemy, son of Lagus, Eumenes, Alexander's archivist, and Lysimachus, a renowned soldier. Without giving up the maintenance of a unitary empire, all share the various territories that make it up: Ptolemy obtains Egypt, where he goes without delay with an army corps. Dissensions are brewing, but they have not yet broken out, because for the moment devotion to the deceased king unites all the heirs in a deceptive unanimity.

Was Alexander buried in the royal necropolis of Macedonia?

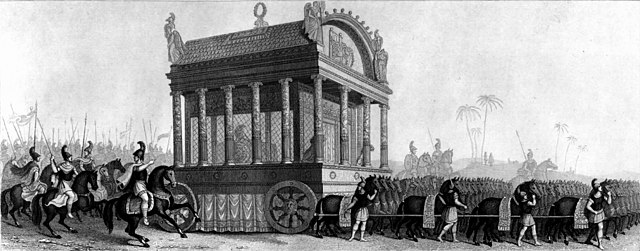

Where are we going to bury Alexander the Great? The Persians, inconsolable at his disappearance, claim his remains, but there is, of course, no question of giving them satisfaction. The Macedonians, who have just divided the empire by carefully leaving the Persians out, plan to send it to Macedonia, to Aïghai (present-day Vergina), where the necropolis of the royal family is located. It is for this, and not to obey customs of Egyptian origin, that Perdiccas brought in embalmers: it is a question of putting the body of the king in condition to withstand a journey of several months. For transport, an extraordinary catafalque will be made, which will take more than a year to build. The royal workshops of Babylon have worked remarkably well and the result, as the crowd can admire, gathered near the gates of the city from where the funeral procession is about to leave at the end of summer 322 BC, is spectacular. The sarcophagus is exactly the shape of the body of Alexander the Great and is made of solid gold.

Or was he brought back to Egypt by Ptolemy?

From a distance, the dust raised by the cavalry squadron escorting it, the tinkling of the innumerable bells with which the catafalque is provided, as well as the mules, also caparisoned with precious stones, announce the passage of the prodigious procession to the populations of the territories crossed, who hasten to run to venerate the remains of the king who defeated them. In his plans to restore the unity of the Empire, Perdiccas entrusts the management of the procession to a sidekick. Fatal error: taking advantage of his absence, and the weakness of the escort accompanying the catafalque, Ptolemy, who for more than a year has firmly taken control of Egypt, advances to meet the procession, under the pretext to pay homage to the great deceased. In Syria, towards Damascus, he takes control and, without losing a moment, leads it into the valley of the Nile, arguing that Alexander the Great would have liked to rest near Amun, the great Egyptian god whom the Greeks likened to Zeus.

It is possible that Perdiccas finally realized the danger of letting Alexander's remains run through the roads; above all, in the meantime, he got angry with Antipater and Craterus who controlled Macedonia. It is therefore probable that he sent, but too late, a counterorder to the procession to return to Babylon; it is even more probable that the one to whom he entrusted the direction of the procession betrayed him for the benefit of Ptolemy. The forces sent by Perdiccas easily join the funeral chariot, which advances very slowly, but they give up engaging in combat against Ptolemy's powerful device. The latter now intends to definitively establish his power in Egypt. He understands how much he can gain from the possession of Alexander the Great's body. Having the Conqueror's burial place in your territory is the best way to appear as your most legitimate and faithful heir. Perdiccas, too, insisted on it and, to recover it, he launched a great expedition against Ptolemy. The ace ! Failing to cross the Nile, his troops were repulsed with great losses and, exasperated, his soldiers killed him before rallying to Ptolemy.

That Perdiccas did not hesitate to commit his army and his life in this way shows the importance of mastering Alexander's tomb. By appropriating the body of the Conqueror, does Ptolemy intend to defend on his own behalf the unity of the empire? More likely, he wants to give a solid symbolic basis to a power in Egypt that he hopes will last: is he already thinking of becoming a king? This is unlikely as long as the existence of parents and descendants of Alexander the Great forbids all of his “heirs” from claiming this title. They won't do it until after 306, when Alexander's mother, brother and son are all eliminated. Ptolemy then has the intelligence not to rush.

Perdiccas had been killed in front of Memphis, a sign that the Conqueror's body was indeed there. Alexander’s remains will remain for a little less than half a century in this capital of ancient Egypt, with a necropolis in Saqqara reserved for the pharaohs. Perhaps its location is revealed by a set of sculptures depicting Greek poets and thinkers, located not far from a tomb which appears to have been first planned for Pharaoh Nectanebo II, but the latter, fleeing the Persian invasion, had left Egypt in 341, so his tomb had remained unused. Ptolemy I is said to have installed there the remains of Alexander the Great, which could explain the curious affiliation later operated by the Roman of Alexander between the last of the pharaohs and the Conqueror. But, over the years, and under the vigorous impulse given by Ptolemy, Alexandria, which is becoming the largest city in the world, also becomes the capital of Egypt.

A man honored like a god

However, for a very long time, the Greeks used to honor the founders of their cities with tombs, located within their walls, and surrounded by special honors; by tradition, too, members of a royal dynasty bestow special veneration on its first representative. It is therefore logical that Alexander the Great, founder of Alexandria and tutelary figure of the royalty created by Ptolemy should one day be buried and honored in Alexandria.

The transfer from Memphis to Alexandria is operated by Ptolemy, but it is no longer the first of the name, as some ancient authors mistakenly say, but the second, as the Greek Pausanias specifies: it probably took place around 280 BC, but the exact location of this tomb is unknown. Now Alexander is a dead man who is honored like a god: his cult is already led by a high priest and parades and ceremonies are celebrated every year in his honor.

A pilgrimage goal

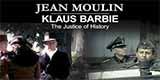

A little over half a century later, here is the fourth Ptolemy, known as Philopator, decides to build a large dynastic necropolis around the tomb of Alexander the Great, which is moved and rebuilt for the occasion. Fought by the kings of Macedonia and Syria, Ptolemy IV, the day after the great victory he won against Antiochus III, felt the need to assert the legitimacy of his dynasty and his ties with the Conqueror. Nothing can illustrate it better than a common necropolis, of which Alexander's tomb will be the center: ancient texts call it indifferently Sôma, "body" or Sèma, "tomb". Thus, the king's body is henceforth the sign of the legitimacy of the Ptolemies and of the world centrality of their capital city. More than ever, the new royal necropolis is becoming a goal of pilgrimage for foreign visitors. The most prestigious of them are the great Romans who each dream of being a new Alexander: Caesar, in 48 BC will be the first, he who had one day wept when he thought that he was coming, without having attained glory, at the age when the Conqueror had died. After him, it will be Augustus, in 30 BC, the day after Actium's victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra, also buried somewhere in Alexandria. The victor is shown the remains of Alexander the Great, who in the operation loses a piece of his nose! To the Egyptians who asked him if he wanted to see the graves of the Ptolemies too, he refused, adding that he had come to see a king and not the dead, an implicit homage to the divine immortality of Alexander; other Roman emperors, Caligula, Hadrian, Septimius Severus, will come to pay homage to the one they consider as their model. The last of these illustrious visitors is Caracalla, in 215. Afterwards, the Sôma disappears in silence.

Towards the end of the 4th century, the Christian John Chrysostom contrasts the oblivion which affects him with the fame of the tomb of Jesus. The tomb of Alexander the Great was therefore destroyed between 240 and 390. On July 21, 365, a very violent earthquake, followed by a devastating tsunami, devastated Alexandria. The chroniclers write with fear of the boats found perched on top of buildings, the temples and porticoes collapsed and littering the ground. It took a catastrophe of this magnitude to bring down a monumental tomb, the upper part of which looked like an imposing mausoleum. In 391, a violent Christian and antipagan riot exploded which resulted in the destruction of the great temple of Serapis, and which perhaps reached what remained of the Sôma: an allusion recently detected in a speech by the rhetorician Libanius would show that the body was then out of the tomb to be publicly exhibited one last time.

Fanciful assumptions

The Conqueror is not ignored by Islam, and Muslim pilgrims will readily locate his tomb in the site of this or that mosque: that of Attarine, which occupies the site of the former church of Patriarch Athanasius, is often cited, as well as that of Nabi Daniel; if the first of these traditions is much older than the other, it is not fair.

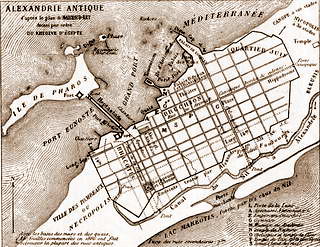

It was not until the mid-nineteenth century and the archaeological plan drawn up, at the request of Napoleon III, by Mahmoud Bey el-Falaki, for research to have a solid basis, which does not mean that there is certainty appointment. For a century and a half, there have thus been no less than 160 proposals for identification. Once all the fanciful hypotheses, which for example locate the tomb in places that were under water in Antiquity, have been eliminated, two proposals for location remain. According to one, the Soma is located near the central crossroads of the ancient city. But according to proponents of the other theory, the description of Strabo, who stayed in Alexandria around 20 BC, requires looking for the tomb much closer to the shore. Doesn't the Greek author write that he "is part of the royal district", which is located by the sea? The problem is therefore the extension that can be given to this district, not to mention the fact that the shore line has shifted since Antiquity.

The mysteries of his final journey

Ironically, we know the catafalque of Alexander the Great better than its destination! Diodorus of Sicily says it took two years to build it: it measures 5 by 3 meters, sits on 4 wheels with gold rims and hubs; a columned building 2.50 meters high each supports a barrel vault; the coffin is protected by 4 painted panels arranged on gilded nets and showing scenes from the life of the Conqueror; at each corner of the roof, a Golden Victory. The whole is pulled by 64 horses. The sequence of events is less certain. If the king's body was first taken to Memphis, then to Alexandria, this abode may not have been the last. The successors of Ptolemy I were able to take him with them to Egypt, to the mausoleum of their dynasty. Unless the Macedonian has finally joined the necropolis of his fathers ...