History of Alchemy : Nicolas Flamel and the Philosopher's Stone

The Philosopher's Stone is an alchemical substance that would transform any metal into gold. The knowledge and means of the time not enough to achieve such a miracle, the scientists began to search for the material likely to accomplish this transformation.

History of alchemy

Originally, alchemy integrated the fields of chemistry, magic, astrology and theology. A specific force which paid particular attention to herbalism had developed in China. It is now known that Western and Far Eastern alchemy goes back to the same sources. It is very likely that European alchemy was the result of myths associated with religious acts and rituals from ancient times. According to a legend, the cradle of alchemy is to be found in Egypt, where the divinity Thoth, under the face of Hermes Trismegistus (thrice-greatest), created art and science. Historically, the origins of European alchemy date back to the 5th century BC.

From this time, hermeticists established theories which did not assert themselves until a century later, such as, for example, the first fundamental medical discoveries and the restriction of observations to the individual elements of Empedocles, or the atomic theory of Democritus. In the 3rd century AD, Zosimos of Panopolis, renowned alchemist, publishes twenty-eight volumes in which he describes the way to transform silver into gold, using a tincture of mercury. Subsequently, the Hermetic teachings first spread from Greece to the Islamic cultural world.

In the 8th century AD, Jabir ibn Hayyan, of which Geber is the pen name, fixes, in one of his writings, a methodology of the experimentation. It establishes the fundamental bases of chemistry and delivers the first descriptions of reaction mechanisms. As such, he is considered one of the founding fathers of chemistry. Geber also mentions a chemical compound used to make gold. For him, this material consists of a small amount of pure sulfur and mercury.

From the 12th century, alchemy developed in Europe. Admittedly, hermeticists of the Middle Ages can often only work in secret, however, many of them enjoy an excellent reputation and are entrusted, generally by a wealthy or influential protector, with research work, notably medical, and the establishment of horoscopes.

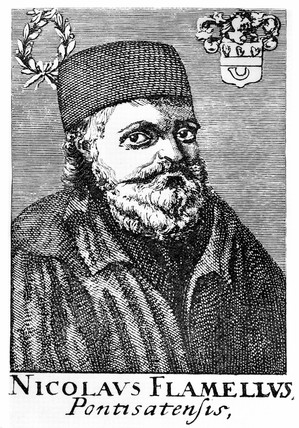

Nicolas Flamel

One of the first alchemists to make a name for himself in Europe was the Frenchman Nicolas Flamel (c. 1330-1418), who is said to have received a book from an angel revealing the secret of the philosopher's stone. So Flamel would have managed to transform silver into gold. Flamel generously distributed his wealth to churches and hospitals which he asked, in return, to be mentioned, for posterity, on the exterior walls.

Some time after the death of the alchemist and his wife, an exhumation revealed that a tree trunk had been substituted for Flamel's mortal remains. It is probably since we associate the philosopher's stone with eternal life. It is said that during the following six hundred years, Flamel was seen alive, so that the myth continues today.

Unexpected discoveries

Flamel's donations and work led, over the following decades, to an intensive quest for the philosopher's stone. However, he was not the first to devote himself to it. Indeed, the Franciscan Roger Bacon (c. 1220-1292), Arnaldus de Villa Nova (c. 1235-1312) and the Majorcan mystic Ramon Llull (c. 1235-1315) had described, long before him, the process of the philosopher's stone . However, Flamel seems to have gone beyond the simple stage of writing: he would have really made gold. So the experiments on metals continued.

The alchemists certainly did not succeed in producing pure gold, but non-noble metals of a pronounced golden hue. However, the products obtained at the end of these experiments have opened up other fields of application. Thus, for example, we attribute the discovery of gunpowder to the Friborg Franciscan monk Berthold Schwarz, in 1353 or 1359. From a historical point of view, this assertion is strongly disputed, because Chinese and Arabs already had powder, long before Schwarz's invention. In addition, Roger Bacon, previously cited, had described it in 1267. However, it is quite likely that the effective discovery of this substance is a matter of alchemy. In 1669, following his quest for the philosopher's stone, the Hamburg alchemist Hennig Brand (1630-1692) discovered phosphorus and in fact, the first element in the history of modern chemistry. In collaboration with the mathematician Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus (1651-1708), the alchemist Johann Friedrich Bottger (1682-1719) discovered the manufacture of Meissen porcelain.

In addition, the scientific knowledge accumulated by alchemy turns out to be extremely precious for the already existing sciences and for those which will appear later. As proof, the observations of Paracelsus, which steered medicine on a new path, or the work of Isaac Newton (1642-1727) who distinguished himself in the fields of physics, philosophy, mathematics and astronomy.

The end of alchemy

The trace of alchemical societies was clearly maintained until the 19th century. Although the twentieth century still benefits from some useful alchemical discoveries in various fields, at that time, the most important achievements already belong to other scientific disciplines such as physics, mathematics, chemistry, biology, medicine, theology or philosophy. In these specialties, fundamental advances, such as the establishment of a periodic classification of chemical elements by Dmitri Mendeleev (1834-1907) and Lothar Meyer (1830-1895) in 1869, rendered many alchemical fundamentals obsolete. In light of current science and technology, many of the research or conclusions of alchemists now seem questionable. Also the image of alchemy will not benefit from a very flattering lighting thereafter.

Now, the notion of alchemy echoes worrying representations of the occult Middle Ages. In addition to representations of mysterious experiences, religious, magical and astrological convergences lead men today to take a considerable step back from this science of origins. It should not be overlooked, however, that many discoveries have benefited other sciences, although the quest for the philosopher's stone has been in vain.

Black sheep

In the past, there were alchemists who, by their quackery or their incompetence, caused considerable damage to their profession, in particular Alessandro Cagliostro (1743-1795) whose elixirs of love, youth and beauty led many clients to divest themselves of considerable sums. Others have been accused of pacting with the devil, like Georg Faust (v. 1480-v. 1540). A third category, carrying out strange experiences, has itself contributed to altering the reputation of the profession. Let us quote, for example, Johann Conrad Dippel (1673-1734) who worked from corpses or parts of corpses and who, one fine day, visibly after a test with nitroglycerine, caused the explosion of a tower in his Frankenstein Castle, a blast that nearly cost him his life.