The Legend of the Lost City of Atlantis

Real Island or Myth ?

The legend of the lost city of Atlantis, which has come down to us thanks to the works of Plato, has all of a fable: the Atlanteans, valorous and prosperous people, would have become corrupt, quarrelsome and greedy, attracting the wrath of the gods. History, however, has fueled the most diverse speculations.

Plato's Atlantis island myth

In his Timaeus dialogue, Plato evokes in 358 BC a story he says he learned from Egyptian priests: "At that time, you could cross this Atlantic sea. It had an island, in front of this passage which you call, you say, the Pillars of Hercules. This island was larger than Libya and Asia combined. [...] Now, in this Atlantis island, kings had formed a great and wonderful empire. Plato points out in his dialogues "the fact that it is not a fiction, but a true story and of capital interest", because the lost city of Atlantis would have been fought by a coalition of Greeks led by Athens: "In the space of a single day and a terrible night, all your Athenian army was swallowed up at once under the ground and, likewise, Atlantis island fell into the sea and disappeared. That is why, even today, this ocean of there is difficult and inexplorable, by the obstacle of the very low muddy bottoms that the island, by swallowing, deposited. The event as evoked by the philosopher is 9,000 years before his time, which places it around 9,600 BC. In a second work, the Critias, Plato describes a rich island divided into ten kingdoms ruled by the descendants of Atlas, son of Poseidon, and his nine brothers. Atlantis would have expanded strongly, conquering by force Mediterranean Africa and the European coast to Italy, thus clashing with the Athenian imperialism. Subsequently, Greek authors, including Herodotus, Thucydides, Diodorus Siculus, took over the story of Atlantis. Two postulates have since guided research: one considers that it is a fiction, a metaphorical narrative without foundation; the other considers that the text refers to real facts distorted by Greek literary usages.

Where is the lost city of Atlantis ?

Since the Renaissance, modern writers have only been concerned with Atlantis location without questioning the veracity of Plato's narrative. In the seventeenth century, Olof Rudbeck, in the direct line of hyperborean patriotism, locates the lost Atlantis in Sweden. Later, during the Age of Enlightenment, the French astronomer Bailly places it in Spitsbergen, archipelago of the Arctic Sea. His contemporary, the theosophist Fabre d'Olivet, imagines it in America. At the end of the 19th century, the immediate west of the Pillars of Hercules, that is to say the Strait of Gibraltar, garners all the favors of scientists. For the purposes of his novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Jules Verne establishes the city of Atlantis on a land now submerged, of which only the Azores and Cape Verde are still visible. In the twentieth century, it is reported off Portugal, near Morocco, in the Bay of Biscay, in North America, in Central America, in the Indian Ocean ... In addition to the landscapes described by Plato, the abundance of an unknown metal, the "orichalcum", constituted a very thin research base. In ancient times, the most abundant minerals were found in Sardinia, southern Spain, in the Isles of Scilly and Great Britain; but archeology has shown no correspondence with any remains. Some authors have advanced - but not proven - the installation of the Phoenicians on the American continent and in the Caribbean. Others have thought possible a displacement of the Earth's crust (Hapgood's theory) towards Antarctica, probable place of the ruins of Atlantis civilization. None of the locations proposed by the partisans of a real Atlantis corresponds, either in place or date, to the Egyptian priests tales reported to Plato.

A real Atlantis or a political fiction ?

The Italian scholar Giuseppe Bartoli is the first, in 1779, to challenge the existence of the lost city of Atlantis. He rightly points out that Plato is neither a historian nor a geologist but a philosopher and that his work should be considered accordingly. The intention of the author of Timaeus and Critias would have been to stage an ideal Republic, a kind of remote and virtuous Athens opposed to a decadent and hegemonic Atlantic invader. This enemy, the city of Atlantis, would be an allegory offering a chronological framework and a place for ideas formulated in The Republic, an earlier work of the philosopher. By the story of Atlantis, Plato would have wanted to give a lesson of civility and good conduct to his fellow citizens and warn them against the risks of decadence and corruption related to their indiscipline, their excessive mercantilism, quarrels and the demagogic spirit of their political mores. To make his approach more credible and his warnings more striking, he needed to create a very colorful narrative context. In his description of Atlantean landscapes, he was thus inspired by Sicily, a region he frequented. This version was supported by the historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet, who sees in Plato a customary of this kind of process consisting in "saying the fictitious by presenting it as the real". The reference to the Atlanteans does not appear in any text before his, which tends to confirm that he himself created this story from scratch. Is the Atlantis myth a modern invention? The best proof would be its journey through history: readers have taken the legend of the lost city of Atlantis seriously only from the modern era, whereas no one had cared for it during Antiquity and the Middle Ages.

The Santorini hypothesis and the Avalon myth

For some historians and scientists, the philosopher's narrative is partly true. This is the opinion of the Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos, who sees similarities between the engulfment of Atlantis island and the collapse of the Minoan civilization (Crete) after the eruption of Santorini, an island near Crete. Atlantis is described as a maritime power whose influence extended as far as Tyrrhenia (Etruria Western Italy) and Egypt. Its ports are frequented by raw materials and goods of all kinds. The Cretan thalassocracy of the legendary King Minos is the only one to match this description in the history of the Greek world: it dominated the Aegean from 2,700 BC before experiencing a sharp decline in the seventeenth century BC. Between 1627 and 1600 BC, the island of Santorini, near Crete, is the victim of a violent volcanic eruption. The phenomenon would have produced a huge tidal wave, with an estimated wave height of 50 m, which would have devastated the northern coast of Crete. This story, transmitted orally by the Egyptian priests, could reach Plato's ears a millennium later. However, neither the place nor the date correspond to his story of Atlantis. Another trail leads into the Atlantic Ocean, where the geological phenomena of marine transgressions and the melting of the polar ice cap have changed the topology of the Atlantic Ocean bottoms at the end of the Ice Age. The Rockall Plateau, in the north-west of Ireland and now immersed, would correspond to Plato's description of the rectangular plain of 600 km by 400 km. This place is present only in the ancient Greek tradition and is widely evoked in Celtic tradition and Arthurian legend as the mythical island of Avalon.

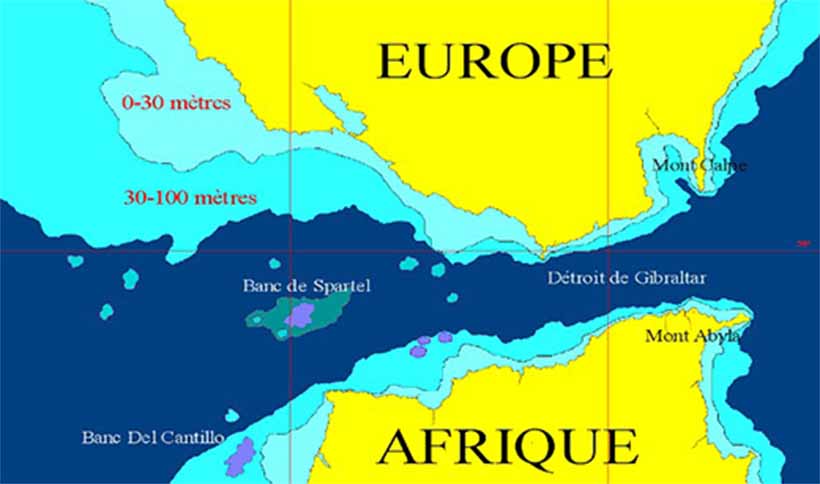

The missing island of Cape Spartel

Due to the lack of a precise location for the site, the Czech geologist Kukal concluded after a serious inventory of existing data that no sunken earth was habitable between 10,000 and 600 BC outside the Madeira area, the Canary Islands and the Azores. However, everything indicates that these archipelagos were only discovered at the time of the Roman expansion of the first century BC. In addition, these volcanic islands with steep sides are narrow and not very hospitable. Remains the area of Gibraltar, these Pillars of Hercules which, although clearly named in the ancient texts, have been previously neglected in the absence of tangible archaeological and geological data. The latest studies on the geological history of the Strait give credit to Plato's history; prehistorians have a new interest in the submerged sites of the Moroccan and Iberian coasts and their geophysical connections, although still poorly known, between the two continents during the Upper Paleolithic. It appears that the pass between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic was then narrower compared to the current strait. The habitable lands extended westward on the emerged plateaus of both continents, and a large number of islands emerged. Today, the best candidate for Atlantis location is the missing island of Cape Spartel, located less than 10 km from the Spanish coast, which was part of an archipelago complete with two islets. Sheltered from the wrath of the ocean, it was occupied by a Paleolithic population whose presence is abundantly attested on the Moroccan, Spanish and Portuguese coasts, and which was submerged by the melting ice at the end of the Ice Age. It is at present time the only realistic track linking the legend of the lost city of Atlantis to a possible scientific truth.