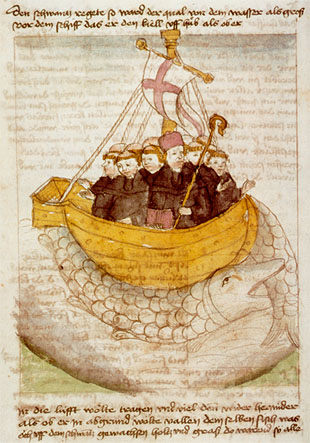

Saint Brendan the Navigator Voyage To The Terrestrial Paradise of America

The Quest For The Isle of the Blessed

A character long considered legendary, the monk Saint Brendan the Navigator is one of the great travelers of the Celtic era. For centuries, the apocryphal stories of his voyages have fascinated medieval readers, convinced that St Brendan had discovered the Isle of the Blessed, in other words, the earthly paradise.

Irish monks navigators in search of the terrestrial paradise : the Isle of the Blessed

In the fifth and sixth centuries, the Celtic monks, whose Catholic tradition of Eastern origin is somewhat opposed to the one Rome tries to impose in continental Europe, turn to the sea. They are trying to convert the Gentiles to the west, which explains the importance they attach to recognizing the Atlantic islands. Moreover, it is recommended, in case they may make at least once the journey to Jerusalem, to go into exile alone or in small groups on a desolate land to do penance and build, eventually, a monastery.

Monks settled in Iceland from the end of the fifth century. But many of them can no longer integrate into the community and spend their time going from island to island. Their wandering is explained by a mad hope: to discover the terrestrial paradise, which a medieval tradition situates, with a strange certainty, on the other side of the Atlantic.

Brendan's first voyages

Around 506, Brendan, a free man born around 484 in Ireland and ordained a priest around 504, lives in Wales. About fifteen years later, he made his first big trip, traveling with a crew to Iceland on board a small skiff. During the journey to this island, considered as the antechamber of Paradise - a sort of modern "purgatory" - he first sees the icy layer that covers the polar ocean and icebergs.

Around 527, this time in the company of two other boats, Saint Brendan goes a first time to the Canaries and then sets sail towards the open sea. How far does this navigation lead him exactly? It can not be said, the various sources tending to mix adventures of this journey with those of the next expedition, much more considerable. However, it appears that, after having progressed painfully, the boats have to face a terrible storm which sinks two of them. When calm returns, Brendan and the survivors see plant debris floating on the water, likely evidence that a western land is nearby. But the sailors, too tired, decide to turn back: finally, the trip does not succeed.

We walked on earthly Paradise !

Fifteen years later, probably in 544-545 (Brendan was almost 60 years old and stays in Brittany), the monk goes on an expedition again. He embarks this time on a solid wooden ship, and, after a new stopover in the Canaries, embarks again on the assault of the Atlantic.

Once again, the texts mention the difficulties of a long crossing on the high seas and mention a storm. Then the sailors discover palm leaves and strange floating hulls covered with fibers – certainly coconuts – on the water.

This detail is very important because the texts that quote it date from a time when these fruits are not yet known in Europe. A few days later, the boat finally arrives in sight of a large tropical island. The description of this island and that of the marine current that bypasses it before heading east suggest that it might be Cuba. Brendan entered there, stayed there indefinitely, then returned to Brittany, which he reached two years after his departure.

The various versions of Saint Brendan voyage, which range from the ninth century to the fourteenth century, claim, for their part, that he has walked the soil of the earthly paradise, also referenced as Saint Brendan's island or the Isle of the Blessed.

Saint Brendan, a historical figure ?

If there is no reason to doubt the existence of Brendan, a navigator-monk in the first half of the sixth century, there is nothing to indicate, on the other hand, that all the exploits that the manuscripts attribute to him come back to him specifically. Indeed, it is possible that the medieval celebrity of the traveling monk and his Isle of the Blessed has made him the father of voyages, or episodes of travel, whose glory would be more appropriately endorsed by other Celtic sailors remained anonymous.

We know how cautiously we must read the hagiographic texts. But the veracity and detail of many descriptions (icebergs and coconuts, for example) clearly show that they were made from real testimonials.

In addition, multiple indications suggest that the Atlantic was frequented much more than has been believed since ancient times. The trip to the American islands is therefore less unlikely than it seems, and Brendan, or some other Celtic sailor, can very legitimately be considered a forerunner of the great Columbus.