Frankenstein's Creature

The Modern Prometheus

This June 16 1816, the weather was rather gloomy on the shores of Lake Geneva and the five English in resort at Villa Diodati had lit a big fire and all candles. Not having much to do to occupy their evening, at that time people had supper at four o'clock in the afternoon, they resolved to entertain themselves by telling each other scary stories.

Lord George Gordon Byron, the master of the house, never parted from a collection of ghost stories called Fantasmagoriana. He opened the small, leather-bound volume, and began to read aloud the story of a young bridegroom whose wife turns into a rotting corpse on their wedding night.

Fertile spirits

Lord Byron's audience consisted of poet Shelley and his future wife, nineteen years old Mary Godwin, Claire Clairmont, Byron's mistress and Mary's sister-in-law, and Byron's personal physician, Polidori. At the end of the evening, Byron offered his companions new entertainment: everyone should write a ghost story. This proposal was to be surprisingly fruitful ; not only did it lead young Mary to write a novel, a lugubrious story (inspired by a dream she made that night) of a corpse to whom life is given back, but it also led Byron himself to sketch a short story called The Vampyre, whose different avatars were to give birth, at the end of the century, to the famous Dracula by Bram Stoker.

The story imagined by Mary was that of a mad scientist who gives life to a monstrous creature. Published anonymously at first in 1818 under the title of Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus, the novel was immediately a great success.

The Vampyre

In The Vampyre, Byron stages a Greek aristocrat pretending to die while making his traveling companion swear to keep his disappearance secret. The later then finds the so-called deceased and sees him engaging in particularly immoral activities; but, held by his oath, he doesn't say anything ...

John William Polidori drew from Byron's story a piece called The Vampyre. Published in a magazine, it was quickly attributed to Byron himself. There was soon a play which was a huge success. London became passionate about vampires, and novelist Bram Stoker swept it all with Dracula. Polidori himself committed suicide in 1821.

Shocking!

In 1826, Henry M. Milner adapted the novel for theater. The monster of the play was so terrible looking that women fainted in the hall the night of the premiere ; it was necessary to review the makeup of the actor, too effective. The play was a big success. As for Mary Shelley, she had not even been consulted.

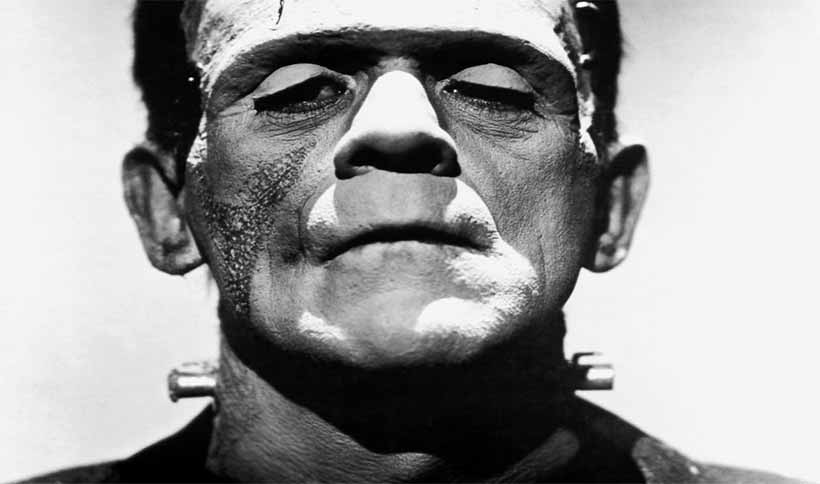

The first film version of Frankenstein dates from 1910; it lasted 10 minutes. In 1915, the Ocean Film Corporation produced a new 60-minute adaptation. But it was not until 1931 that the character invented by Mary Shelley really gained universal notoriety as well as a face, that of Boris Karloff, thanks to a Hollywood Universal Studios movie directed by James Whale. Whale had already achieved great success with his Dracula, performed by Hungarian actor Béla Lugosi. Frankenstein was an all-found sequel; Lugosi was of course foreboded for the lead role, but declined the offer. After incarnating the refined and sinister aristocratic count Dracula, Lugosi didn't want to play the part of a thick brute expressing himself only by grunts.

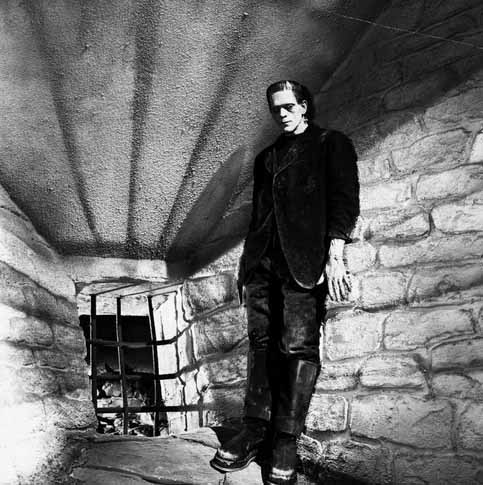

The incarnation of a monster

James Whale had barely survived Lugosi's refusal when he noticed in the studio canteen an English actor named William Pratt, a tall well-marked fellow with deep-set eyes. He agreed to the shooting of a test scene. Makeup artist Jack Pierce, who was a virtuoso, immediately saw all the potential he could get out of this energetic face.

To spare his family the disgrace of counting an actor in its ranks, his brother was a prominent diplomat, Pratt had already adopted Boris Karloff's stage name, patibular at will.

In the role of the monster, he proved to be sensational. It matched wonderfully with the sets and the gothic atmosphere of the film. Until his death in 1969, Boris Karloff was to remain the most famous bad guy in Hollywood.

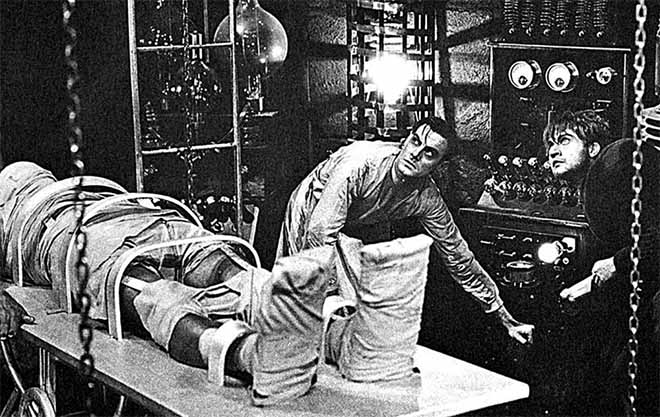

Mary Shelley (who died in 1851) wouldn’t have appreciated that Hollywood turned her hero into a symbol of evil. The creature of the novel is a tragic character, a tormented human being, aspiring only to one thing: the love of other men, which his monstrous ugliness forbids him to obtain. He is in no way an incarnation of evil. Similarly, Mary Shelley's Victor Frankenstein has nothing to do with the mad scientist of the film; he is a sort of romantic and tragic idealist, much closer to the man who married Mary, poet Shelley, than the frenetic genius embodied by Colin Clive on screen.

Frankenstein Castle

Is the mad scientist of the novel entirely the product of Mary Shelley's imagination? Not quite. The young novelist was inspired by two real characters: the first was a German alchimist and doctor, Johann Konrad Dippel, born in 1673 in a fortress near Darmstadt, Frankenstein Castle, the reference is explicit. The second was an Englishman named Andrew Crosse who claimed to have created life in his laboratory.

Coming from a line of Lutheran pastors, Johann Dippel showed early signs of intelligence. A student of theology, he acquired the reputation of being a brilliant brain, he concealed, it is said, a certain arrogance which would cause him some troubles later on. Initiated to alchemy, he tried in vain to make a fortune by creating gold. One may nevertheless judge of his talents as a chemist by the fact that he invented the dye called Prussian blue.

In 1707, he went to Leyden to study medicine which he then successfully practiced in Amsterdam. Dippel, however, made the mistake of meddling in politics which led him straight to prison on the accusation of heresy. He then led a traveling existence between Norway, the Netherlands and Germany, where Count Wittgenstein set up an alchemy laboratory. Dippel claimed to have developed an elixir of longevity: early in 1734, when he was fifty-one, he prophesied that thanks to his invention he would live until 1808. Two months later, he was dead.

The other Frankenstein

The other character that could be considered the real Dr. Frankenstein was Andrew Crosse. Mary Godwin and Shelley really met him through a mutual friend; they even attended one of his lectures on electricity and this two years before Mary began writing her Frankenstein. But it was only twenty years after the publication of her novel that Crosse realized the famous experience that made him one of the most hated men in England. He was accused of trying to create life in his laboratory. He seemed to have succeeded, but he paid dearly for his success. Honored by both the scientific world and his neighbors, he found himself practically a prisoner in his own home. When he died in 1855, he took his secret with him to the grave. This episode remains one of the strangest in the history of science.

May it live!

The storm scene, in which Frankenstein uses lightning to bring the monster to life, is one of the most spectacular in Frankenstein. Electricity was at the heart of Lacrosse's experiments. In Mary Shelley's novel, Dr. Frankenstein uses chemistry, alchemy, and electricity to breathe the spark of life into his creature.