Alan Turing And The Enigma Code

The Spy War

The Enigma machine was invented between the two great wars for civilian applications. The Dutch engineer Arthur Scherbius exhibited it for the first time at the International Congress of the Postal Union in 1923. The phenomenon of industrial espionage, which was booming in these years, convinced him of the usefulness of his invention. However, if it does not hold the attention of industrialists, it is immediately bought by the staffs of the armies of different countries, including Germany, Japan, Poland and the United States. Its machine is so complex that it can produce, thanks to its three rotors, 150 million million different combinations. This means, among other things, that it can be used by one of the armies of the acquiring states, without the others being able to decode the encryption, not knowing which of its innumerable combinations is used.

Flowing money

Sometimes the most innocuous characters play a major role in complex situations. Indeed, the Germans could have lost the war because of an extravagant character, great lover of women and luxuries of all kinds, named Hans-Thilo Schmidt. Driven by purely pecuniary motives, he sold the Enigma manuals to the French secret services in 1931, at a time when Hitler was not yet in power. He thus transmitted information to the Allies until 1943, when he committed suicide in prison to escape the torture of the Nazis. Unfortunately, Enigma's countless combinations make his information ineffective. The French, for their part, unable to decipher them, resell this information to the Polish secret services, which painstakingly manage to decipher messages intercepted months before.

In 1937, Nazi Germany plans the invasion of Poland which will be implemented two years later, which will start the Second World War. To make their communication system even more secure, the Germans add two more rotors to their machine (for a total of five, in all) and change codes several times a day. In terms of espionage, the war is therefore won with speed of decryption.

A life-size chess game

Bletchley Park, Buckingham County: In this Victorian-era mansion, a game of chess is played between Allied and Axis forces. The stake is colossal: world domination. From 1938 until the end of the war, a team of mathematicians, engineers and computer scientists of several nationalities spent all these years trying to decipher the codes of the infernal Enigma machine. These are years when victories alternate with defeats. While in Bletchley Park we try to decipher the codes faster and faster, in Berlin we change them more and more frequently. However, despite the best efforts of the Germans, the England-based team is getting more efficient day by day. Thanks in particular to the singular genius of characters like Alan Turing, in whom we recognize today the precursor of the artificial intelligence of our modern computers, not even imagined at the time.

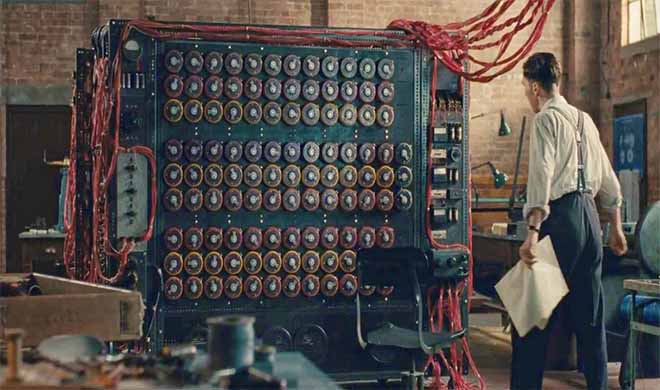

Enigma Machine and Alan Turing

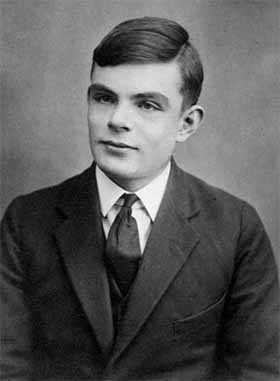

In 1940, Alan Turing invented what would be called “bombs”. These are machines close to Enigma which, thanks to a large number of rotors rotating at full speed, calculate all the possible combinations in no time. If in high school he failed his math exams - his teachers criticized him for wasting his time in unnecessary research and for being messy and dissipated - at 28, Alan Turing is the head of the group of researchers at Bletchley Park. However, his extravagance makes him a disturbing character. At the end of the war, medals and honors were followed by a conviction for obscenity which put him on the margins of society. After a severe nervous breakdown, he died in 1954, under unsolved circumstances, at the age of only 42. We still do not know if he committed suicide or if he was eliminated by the secret services who saw in him a danger because of the defense secrets he held. Recently, his memory has been rehabilitated and a statue has been erected in his honor.

Secret code hunt

The English armed forces played a decisive role in the course of the war because, despite the many casualties, they often captured German ships and submarines with the Reich cipher codes and Enigma machines on board. Recently, an American film sparked controversy on this point. In this fiction, it was indeed argued that it was the Americans who had appropriated the Enigma machines, despite the fact that most of their fleet was fighting on the Pacific front. The English, for their part, until the 1970s preferred to attribute the credit for so many victories to their generals rather than to the men of Bletchley Park. Churchill himself has been accused of questionable acts and in particular of not having prevented certain enemy attacks, with full knowledge of the facts - with the consequent human losses -, so that the Germans do not suspect that the Enigma code had been deciphered.

This is not the first time that Churchill has been the subject of this type of accusation. A few years ago, the opening of secret military archives uncovered documents which led some scholars to say that Churchill was aware of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and that he would not have warned Washington, because he wanted the United States to go to war as quickly as possible.

A major role in the conflict

In other words, Enigma not only evokes the machine invented by engineer Scherbius, but also the hard work of the men who worked to decipher its codes at Bletchley Park and to whom, presumably, we owe the outcome of the war. What would have happened if the Allies had lost the war? Fortunately, the Soviets invaded Berlin at the right time. It is known today that Nazi Germany had long been working on new murderous projects and was developing jets and missiles, even the atomic bomb. It even seemed that these weapons were close to being operational. We also know that in May 1945, Berlin had taken the decision to make radical changes in the encryption codes of Enigma. How would the men at Bletchley Park have reacted when they discovered that their research was no longer useful? Would they have found the courage to start all over again?

What is cryptography?

Cryptography deals with methods of coding a message so that it can be read only by those who have the reading key. The word cryptography comes from the Greek kryptos which means “hidden” and graphein which means “to write”. The custom of writing coded messages is as old as the world. The Hebrews already used the Atbash code; Julius Caesar, meanwhile, is considered the inventor of homonymous encryption, a method that seems childish today. Over the years, the encodings have become more and more sophisticated, from the so-called sliding one to the mono-alphabetic one, from which the poly-alphabetic ones are then derived. Among the latter, the most complex is undoubtedly the Vigenère cipher, widely used until 1863, when the Prussian colonel Friedrich Kasiski succeeded in deciphering it. Later, in 1918, Gilbert Vernam perfected the Vigenère method, which made it possible to evolve towards the complexity of current systems. The counterpart of cryptography is cryptanalysis, which studies the methods of decoding encrypted messages.